Summer 2017: New movement restrictions in Hebron heighten isolation of Palestinian neighborhoods

Since the mid-1990s, the Israeli military has imposed a policy of segregation in the center of Hebron. As part of this policy, major streets in the area have been declared off limits to Palestinians, some entirely, while in others, pedestrian Palestinian traffic is allowed. Nonetheless, as detailed below, in May 2017 the military added new measures to the already severe limitations on Palestinian movement in the area.

As a result of this policy, thousands of Palestinians have left downtown Hebron, and what used to be a lively regional trade center is now practically a ghost town. The residents who have not moved out suffer violence and daily harassment at the hands of Israeli security forces and the settlers who have moved in under their protection.

These drastic measures, which have taken a toll on tens of thousands of Palestinians, constitute collective punishment. The Palestinians who still live in the area are denied the ability to lead normal lives and their daily experience is unbearable. In imposing this policy, Israel is effecting a silent, ongoing transfer of Palestinians from the heart of Hebron.

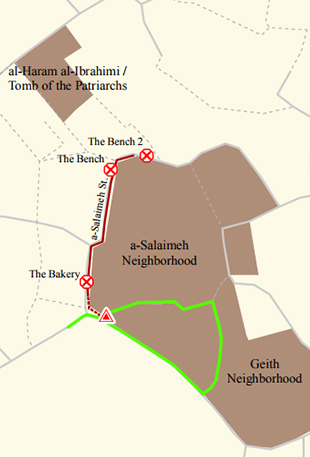

Segregation fence along a-Salaimeh Street extended

A major road on which Palestinians are barred from driving runs through the neighborhood of a-Salaimeh and leads to al-Haram al-Ibrahimi (the Tomb of the Patriarchs). There are checkpoints at both entrances to the street: the Bakery Checkpoint to the west and the Benches Checkpoint to the north. Over the years, the military has occasionally changed the procedures at the Bakery Checkpoint. In 2012, the military installed a fence along the road, dividing it in two. The broad paved part was left open to Jews alone, in cars or on foot, while Palestinians were only allowed to walk along a derelict side path that ends in a small stairway. The practice was cancelled in March 2013, after B’Tselem published footage of Border Police officers explaining that using the paved part of the road is permitted to Jews alone. However, the fence was left standing.

A major road on which Palestinians are barred from driving runs through the neighborhood of a-Salaimeh and leads to al-Haram al-Ibrahimi (the Tomb of the Patriarchs). There are checkpoints at both entrances to the street: the Bakery Checkpoint to the west and the Benches Checkpoint to the north. Over the years, the military has occasionally changed the procedures at the Bakery Checkpoint. In 2012, the military installed a fence along the road, dividing it in two. The broad paved part was left open to Jews alone, in cars or on foot, while Palestinians were only allowed to walk along a derelict side path that ends in a small stairway. The practice was cancelled in March 2013, after B’Tselem published footage of Border Police officers explaining that using the paved part of the road is permitted to Jews alone. However, the fence was left standing.

In January 2015, the military reinstated the segregation along the road, permitting only Jews to use the main part of the road and diverting Palestinian residents of the neighborhood to the narrow side path, as documented by B’Tselem here.

In May 2017, the military expanded the segregation by putting up a fence that blocks Palestinians from accessing another section of the road, which leads to the Gheith neighborhood. A locked gate was installed at the end of the fence. Initially, a Border Police officer was stationed at the spot, opening the gate for Palestinians wishing to go in and out of the neighborhood. Yet within two days, the military locked the gate and left it closed for three days in a row. A Border Police commander informed several neighborhood residents who had gathered at the gate that it would be kept locked all night, from midnight to 6:00 A.M., and that from 6:00 A.M. to midnight the gate would be opened by Border Police stationed at the nearby Bakery Checkpoint, when they felt enough people had gathered there to suit them.

Testimonies given by area residents to B’Tselem indicate that even this procedure is not implemented: For instance, from 15 through 21 June, the gate was kept locked and Border Police would allow no residents through the gate. Since then, on some days the Border Police have left the gate open for many hours and residents could go through freely, while on other days the officers only let them through for several hours, entirely arbitrarily. These conditions keep the residents in a state of constant uncertainty, never knowing whether or not they will be able to get through. The alternate route takes far longer, runs through dark alleyways, up and down flights of steps, is hard to negotiate, and is dangerous at night. (Read testimonies)

Video of alternate route local residents must take when the gate is locked. Click here to view the uncut footage of the entire alternate route.

Palestinian pedestrians barred from using southern entrance to Wadi a-Nasara neighborhood

Some 45,000 Palestinians live in Wadi a-Nasara, al-Hareqa and Jabal Juhar – three Palestinian neighborhoods in the southern part of Hebron. The settlement of Kiryat Arba was established in close proximity in 1972, and settlers make their way to al-Haram al-Ibrahimi (the Tomb of the Patriarchs) along the main road connecting the neighborhoods, which the military calls ‘Worshipers Route’. In 2002, aAfter Palestinians killed twelve members of the Israeli security services on that road in November 2002, the military erected a 300 meters barrier between Wadi a-Nasara and the road. Since that time, the military has forbidden Palestinians to enter this section of the street, forcing them to walk through a neglected field by the side of the road.

Some 45,000 Palestinians live in Wadi a-Nasara, al-Hareqa and Jabal Juhar – three Palestinian neighborhoods in the southern part of Hebron. The settlement of Kiryat Arba was established in close proximity in 1972, and settlers make their way to al-Haram al-Ibrahimi (the Tomb of the Patriarchs) along the main road connecting the neighborhoods, which the military calls ‘Worshipers Route’. In 2002, aAfter Palestinians killed twelve members of the Israeli security services on that road in November 2002, the military erected a 300 meters barrier between Wadi a-Nasara and the road. Since that time, the military has forbidden Palestinians to enter this section of the street, forcing them to walk through a neglected field by the side of the road.

In 2002, the military also installed a gate separating Wadi a-Nasara from Jabal Juhar and al-Hareqa. At first, Palestinians were prohibited from crossing through at the gate at all times. After about a year, the military began allowing Palestinian pedestrians through. In 2014, only some 100 residents were issued permits to drive through the gate. Following the wave of violence that began in late 2015, even these permits were revoked. Since then, Palestinians have been allowed through the gate on foot only. Soldiers were sometimes stationed there on weekends and on Jewish high holidays, restricting Palestinian passage.

In May 2017, the military returned to barring all Palestinian movement through the gate, whether by car or on foot. The prohibition is enforced by soldiers who are regularly stationed at the gate. This forces residents of Wadi a-Nasara to take a 3-km detour, even though some of them live just 200 meters from the gate. In late June 2017, the soldiers began sporadically letting Palestinian pedestrians through again.

‘Eziyah ‘Iz a-Din, 70, a widow from Wadi a-Nasara, spoke with B’Tselem field researcher Musa Abu Hashhash on 22 May 2017. In her testimony, she related how a soldier blocked the way to her home when she was returning from a visit to her daughter’s in the nearby neighborhood of Jabal Juhar, as seen in the video above:

I live with my six married sons in the neighborhood of Wadi a-Nasara. I have a married daughter who lives in Jabal Juhar. To visit her, I usually walk from home to the locked iron gate along the road, near the settlement of Kiryat Arba (the al-Hareqa neighborhood). From there I take a taxi to her house. Earlier today, I set out with three of my daughters-in-law to visit her. We walked to the gate and from there were driven to her house. On our way back in the afternoon, there were soldiers at the gate. That’s not unusual. What surprised me, though, was that one of them told me to turn around and go back. I refused and explained that I was on my way home. I pointed out my house to show how close it is. The soldier wouldn’t let us through and started shouting at us. It was hot and I thought what a long way we’d have to walk if they didn’t let us through – three or four times more than the direct route, because we’d have to walk through the houses of Jabal Juhar until the end of road, which is blocked off with concrete blocks in the Jaber neighborhood, and from there up the path to our house. The police officers kept yelling at us to go back. I sat down on the concrete blocks next to the gate and refused to budge.

I sat there for about five minutes and then the soldier apparently understood that I wasn’t going to give up and agreed to let us through the gate. But he stopped us from walking straight on home, and instead ordered us to walk along a field full of thorns by the side of the road and make our way through the houses. Still, that was easier than walking through Jabal Juhar. We weaved our way through the houses until we got home. I am an elderly woman and this situation is not easy for me.

Main street of Wadi a-Nasara, reserved exclusively for settlers. On right: the barrier fencing off the overgrown, stony field designated for Palestinian pedestrians. Photo by Manal al-Ja’bri, B’Tselem, June 2017

Jihad Hussein Lafy a-Najar, 38, married, a resident of Wadi a-Nasara, related in a testimony she gave to B’Tselem field researcher Manal al-Ja’bri on 22 June 2017:

I live with my husband and his entire family in the neighborhood of Wadi a-Nasara. Since May 2017, we haven’t been allowed through the gate near the al-Hareqa neighborhood. The soldiers there don’t let us move between the neighborhoods through the gate, so we have to take long detours. My sister Hala and other relatives live in Jabal Juhar, so the gate cuts me off from them. Every time I visit them, the soldiers at the gate make me take a three-kilometer detour. For instance, a month ago, my sister Hala said she was coming over. I waited for her and then she called and told me that the soldiers wouldn’t let her through to get to my house, which is only 500 meters away from the gate. I immediately went down to the gate and tried to persuade the soldier to let her through. I explained that my house is close by. When I asked why she wasn’t allowed through, he said it was because kids were throwing stones at the settlement of Kiryat Arba. I argued with him for about ten minutes and finally convinced him to let me cross over to her side, so we could take the long way around together.

This checkpoint makes our lives – everything we want to do – very difficult. If you want to fix something in the house, it’s hard to get equipment across. Sometimes there’s no running water, and we have to buy water tanks. Because of the checkpoint, we now have to lug them all that long way, or coordinate with the Palestinian DCO to let us through in a car, on a one-time basis. This is how we live.

Zahiyah Mahmoud a-Rajabi, 35, a married mother of three from the Gheith neighborhood, related in a testimony she gave to B’Tselem field researcher Manal a-Ja’bri on 30 May 2017:

We live at the entrance to the Gheith neighborhood, 30 meters from the Bakery Checkpoint. In this area, close to al-Haram al-Ibrahimi (the Tomb of the Patriarchs), we’ve had checkpoints all around us for years. There are four of them near my house: the Bakery, Checkpoint 160, the Pharmacy, and the Benches. On Thursday evening, 4 May 2017, we were surprised to see Border Police officers and a Civil Administration officer building an extension to the fence that runs down a-Salaimeh Street. They put up a 3-meter-high fence with a gate just at the entrance to our neighborhood. At first, a police officer was stationed there and he would let us through. Then they started limiting the hours. The commander in charge of the area informed us that only from six in the morning to midnight we could come to the gate, press a button, and an officer would come down to unlock it.

That did not happen. The police didn’t stick these rules. For example, about a week ago, I went out of the neighborhood in the early afternoon with my husband and kids, to have Ramadan dinner at my parents’. On our way back home, we got to the gate at around 10:40 at night and it was locked. Another family from the neighborhood was also there, waiting to get through. We asked a police officer up at the Bakery Checkpoint to unlock the gate, but he said he wasn’t under any obligation to open it at that hour. We argued with him, but he refused. A Border Police vehicle passed by with a commander inside. We asked him, too, but he ignored us.

In the end, we had to take the long way around, which has stairs and is about 500 meters long, even though we live just 30 meters from the gate. The restrictions on movement in the Old City of Hebron make our lives miserable. It’s especially bad at Ramadan, when we can’t accept invitations from relatives or have them over to break the fast in the evening together. Ramadan last year was the same – no one accepted our invitations because it’s so hard to get in and out, with the harsh regulations at all the checkpoints around our house.

Nael Fakhuri painting his pottery. Photo by Manal al-Ja’bri, B’Tselem, 19 June 2017

Nael Rateb Fakhuri is a 40-year-old potter and father of nine who lives in the Gheith neighborhood, just across from the gate installed by the military. In a testimony he gave to B’Tselem field researcher Musa Abu Hashhash on 19 June 2017, he related the following:

I live in the Old City of Hebron. The Bakery Checkpoint is right opposite my house, across the road. I have seven sons, the eldest is 17, and two daughters – the younger one, Maysaa, is three years old. I own a pottery workshop on al-Fahs Street, in the southern part of Hebron.A few weeks ago, the military extended the separation fence in our neighborhood – a-Salaimeh/Geith – by about thirty or forty meters, so now it reaches right up to our house. They put in a gate at the end of the fence. At first, they left it open, but then they started locking it. The fact that it’s locked at night has made all our lives in the neighborhood unbearable. The main street is the shortest way to get to al-Haram al-Ibrahimi (Tomb of the Patriarchs) and to the market. During the month of Ramadan, people are out and about throughout the night and evening, going to prayers, shopping or visiting. Now, to get in and out, we all have to take a long way around through alleys and stairways, carrying our groceries. Since they locked the gate, my wife has been very wary of going out at night.

I often bring home pieces of pottery I’m working on to sell in the area. Before they extended the fence, I used to bring the merchandise by car to Checkpoint 160, and from there transfer it to a cart and wheel it home. Now I can’t even do that. My sons have to help me drag the cart along alleyways and dozens of stairs. By the time I get home, I’m exhausted. My son makes the trip with the cart more than once a day. If they will go on keeping the gate locked, I’ll have to stop bringing the pieces home.

I also have a few heads of livestock, which I keep by our house. Since the gate’s been locked, I’ve had to carry feed the same way – dragging the cart on a long roundabout way between houses.

Last year, I invited relatives over to break the Ramadan fast together. That day, the military closed the checkpoints on the way to our house: the Pharmacy Checkpoint and Checkpoint 160. None of our guests could get through. We had to give away most of the food we’d prepared. I learned my lesson and this year we didn’t plan a feast. We were also very hesitant about accepting invitations to Ramadan dinners outside the Old City. Our lives have become sheer hell, but we have no choice. We have to stay here – it’s our house and we own it. It’s not a rental. I can’t afford to leave it and rent a place somewhere else.

Muhammad Kamal Muhammad a-Salaimeh, 53, a married father of eight from a-Salaimeh neighborhood, related in a testimony he gave to B’Tselem field researcher Manal a-Ja’bri on 18 June 2017:

I live with my wife and kids in a-Salaimeh neighborhood, opposite the police station of al-Haram al-Ibrahimi. We’re surrounded by checkpoints on all sides, and we have to go through them daily.

My sons and I make shoes at a workshop at the front of our house. It’s our family’s only source of income.

It’s a real nightmare when we have to get something to the house, whether it’s groceries or furniture or raw material for work. The Border Police officers at the checkpoints detain us with security excuses and search us. We can’t get to the house with a car and have to carry everything, including goods for making the shoes, in a small cart.

Since they extended the fence and installed the gate, things have got worse. The gate is too narrow for our cart. When it’s open, I have to unload everything on one side of the gate, push the cart through on its side, and then put everything back inside. Also, the police keep the gate locked on Fridays and Saturdays, as well as whenever the settlers celebrate a holiday or have a wedding in the courtryards of al-Haram al-Ibrahimi.

On Thursday, we were surprised to discover that the gate was closed permanently. I don’t know how I’ll get material in for work or carry it to my workshop. I can’t take the cart through the Gheith neighborhood because it’s full of stairs, plus that would add at least 700 meters to the trip. Also, my wife and daughters are afraid to pass through there because it’s quite dark and sometimes drug addicts hang around there.

I don’t know how long we’ll be able to survive like this, cut off from the world and even from our own families. We’ve stopped inviting family over for the evening Ramadan dinner, and other things, because we’re afraid they won’t be able to come. We love the atmosphere during the month of Ramadan – going to prayers after breaking the fast, or dawn prayers, or having guests over and being hosted by others for dinner. Living in this closed-off area, we can’t do any of that. We live like prisoners in a huge prison. It’s intolerable, and things have got worse since they tightened the restrictions – inspecting people even more at checkpoints and closing off the way to our house.

I’m angry that my house has become a kind of prison for me and for my family, while the settlers and their families enjoy the freedom to go wherever they want. They drive around freely and walk around the yard of al-Haram al-Ibrahimi. They have weddings and other festivities there, with loud music that keeps us up, sometimes until the early hours of the morning.

To make matters worse, we can’t marry our sons and daughters to families outside our area. Those families don’t want their children to marry ours because they want to spare them the daily suffering we endure just from living in this area. Four houses were deserted three years ago. I think the occupation authorities are purposely being hard on us and making our lives hell in order to empty the neighborhood of Palestinians.